Quick Answer: India's deepfake regulation (effective November 2025) mandates 10% screen labels on all AI content. Platforms must verify user declarations and deploy detection tools. The catch: screenshots bypass labels instantly, and AI detection accuracy sits at only 65-70%. Technically unworkable, say practitioners.

The Screenshot That Breaks Everything

India's new law says every AI image needs a 10% label that can never be removed. But a screenshot can defeat it in seconds.

Take that in for a moment. The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) spent months crafting rules requiring permanent, unremovable identifiers on all synthetically generated content. And the entire framework crumbles the instant someone presses two buttons on their phone.

This is the core absurdity of India's IT Rules amendment on deepfakes, which came into force on November 15, 2025. The intent is noble. The execution? As AI practitioners from The Fifth Elephant told MeitY, it's "technically unworkable."

What the Law Actually Says

The amendment to the IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 introduces India's first legislative definition of "synthetically generated information." According to Law.asia, this covers any information "artificially or algorithmically created, generated, modified or altered using a computer resource, in a manner that appears reasonably authentic or true."

Here's what platforms and creators must do:

For Visual Content: Labels must occupy at least 10% of screen area. They must be permanent and cannot be removed or modified.

For Audio Content: Labels must cover the initial 10% of duration. Again, permanent and unremovable.

For Platforms: Significant Social Media Intermediaries (those with 5 million or more users) must require users to declare if content is AI-generated. They must also deploy "reasonable technical measures" to verify these declarations.

The rules sound comprehensive. On paper, every AI-generated image floating through Indian social media should be clearly marked. Reality has other plans.

The Technical Reality Check

You open Midjourney. You generate an image. The platform dutifully adds a 10% watermark. You post it on X. Someone takes a screenshot. The watermark is now just pixels in a new image file. All metadata: gone. All provenance signals: erased.

According to practitioners who spoke to Medianama, this isn't an edge case. It's the default behaviour of how content moves online. Screenshots, compression, re-encoding, screen recording - these are routine actions that strip or degrade provenance signals, "making these controls unreliable in practice."

The enforcement mismatch is brutal. Compliant platforms add labels. Honest creators mark their work. And malicious actors? They simply use open-source or locally hosted models that don't add labels in the first place. Or they "launder" content across platforms where provenance no longer holds.

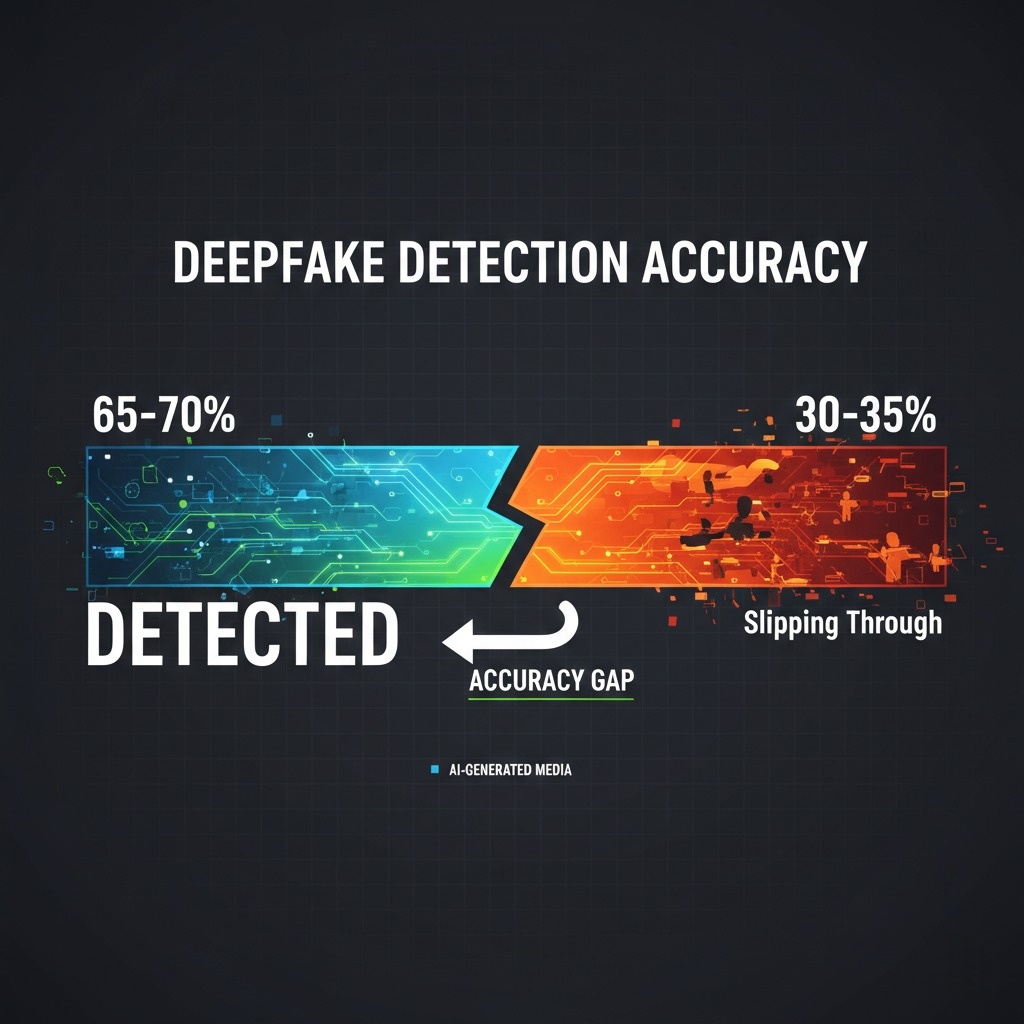

Even when platforms try to detect synthetic content, the tools aren't ready. According to 360info, AI tools detect deepfakes with only 65-70% accuracy, limiting large-scale identification. False negatives let harmful content through. False positives take down legitimate satire and art.

The Grok Test Case

We didn't have to wait long for a real-world stress test. In early January 2026, users on X discovered they could prompt Grok, the platform's AI chatbot, to generate sexualized images of real women. According to TechCrunch, the resulting deepfakes spread rapidly.

MeitY issued a directive to X on January 2, 2026, giving the platform 72 hours to take action. The ministry's letter warned that failure to comply could strip X of its "safe harbour" protections under Indian law.

X's response was swift. According to The Week, the platform deleted over 600 accounts and removed approximately 3,500 posts. They restricted Grok's image generation capabilities and made the feature available only to paid subscribers - "adding a layer of protection," they said, "by helping ensure that individuals who attempt to abuse Grok can be held accountable."

But here's the telling detail: the harmful content went viral before any labels or detection systems could stop it. The damage happened in the gap between creation and enforcement. And that gap, with current technology, cannot be closed.

The Overbroad Definition Problem

The Internet Freedom Foundation has raised another fundamental concern: the definition is too wide.

IFF argues that covering "any algorithmic creation or modification that reasonably appears authentic" sweeps in routine, non-deceptive uses of software. Photo editing. Audio cleanup. AI writing assistants. Virtually all online content creation involves some algorithmic processing now.

The rules contain no explicit exceptions for satire, news reporting, academic research, or artistic expression, according to TechPolicy.Press. These are forms of speech at the heart of democratic participation. Treating them all as suspect creates what IFF calls "compelled speech" - forcing creators to add disclaimers regardless of context.

The organisation also highlights a "policy dichotomy." While India tightens controls on synthetic media, it simultaneously promotes facial recognition initiatives like the IndiaAI Face Authentication Challenge. The same technology that enables deepfake detection also enables mass surveillance.

How This Compares to the EU

India isn't alone in struggling with synthetic media regulation. The EU AI Act's Article 50 takes effect in August 2026 with similar transparency obligations.

But there are key differences. According to the European Commission's draft Code of Practice, the EU approach focuses on machine-readable metadata rather than visible labels. It proposes an "EU common icon" - a small indicator rather than a 10% screen takeover. And critically, it exempts content created for purely personal, artistic, or satirical purposes.

The EU also acknowledges technical limitations. Its framework emphasizes making labels "effective, interoperable, robust, and reliable as far as technically feasible" - that last phrase doing a lot of heavy lifting.

India's rules, by contrast, mandate specific percentages and absolute prohibitions on removal. No feasibility caveats. No artistic exemptions in the published text.

What Platforms and Creators Should Actually Do

Given that the law is in force but enforcement remains uncertain, here's the practical reality:

For Platforms: Implement visible labelling where technically possible. Document your "reasonable technical measures" even if they're imperfect. The Grok incident shows MeitY is willing to act fast when content goes viral.

For Creators: If you're using AI tools on compliant platforms, the labels will likely be added automatically. If you're using open-source tools, you're operating in a grey zone. The rules technically apply to all AI content regardless of source.

For Everyone: Understand that these rules target platforms more than individuals. The due diligence burden falls on intermediaries. But if your AI content causes harm, the lack of labels could become evidence against you.

The Real Solution Nobody Wants to Hear

Critics like those quoted by 360info argue that India's approach is "technically unfeasible, socially naive, and legally clumsy." Their proposed alternative? "Invest in building an informed, critical citizenry."

It's not a satisfying answer. Media literacy programs don't generate headlines or satisfy public outrage after a celebrity deepfake goes viral. But they might be more effective than rules that screenshots can defeat.

The uncomfortable truth is that no technical solution can perfectly separate authentic from synthetic content in a world where the tools to create and modify are widely available. What we can do is build systems that attribute content to sources, enable rapid response when harm occurs, and educate people to question what they see.

India's rules attempt all three, but lean heavily on technical controls that may not survive contact with reality. The Grok incident was the first major test. It won't be the last.

We'll update this piece as MeitY clarifies implementation guidelines or courts challenge the rules. For now, the law is technically in force. Whether it's technically possible is another question entirely.

![India's Deepfake Law: 10% Labels That a Screenshot Can Defeat [2026]](https://techdodo.in/storage/articles/deepfake-regulation-india-2026-enforcement_1768559530_696a13aa0fffc_medium.webp)