Quick Answer: Apple refused India's mandate to pre-install the Sanchar Saathi app on iPhones, and the government withdrew the order within 5 days. No, Apple wasn't going to "leave India"—that was never a real possibility. But this standoff revealed exactly how much leverage a ₹75,000 crore annual business gives a company when negotiating with governments.

For about 120 hours in early December 2025, tech headlines screamed about an impending collision between the world's most valuable company and the world's largest democracy.

India had ordered all smartphone manufacturers—Apple, Samsung, Xiaomi, the lot—to pre-install a government-developed "cyber safety" app called Sanchar Saathi on every device sold in the country. The app couldn't be deleted. Its functions couldn't be disabled. Manufacturers had 90 days to comply.

Apple's response, relayed through sources to Reuters, was refreshingly blunt: "Can't do this. Period."

What followed was a masterclass in corporate-government brinkmanship that ended exactly how anyone paying attention knew it would.

What Was India Actually Asking For?

Let's start with what Sanchar Saathi actually does, because the app itself isn't sinister.

Launched as a web portal in May 2023 and as a mobile app in January 2025, Sanchar Saathi is genuinely useful. It lets you check how many SIM cards are registered to your Aadhaar, report stolen phones, verify if a device's IMEI is genuine, and flag suspicious calls through a feature called Chakshu. By December 2025, the app had 1.4 crore downloads and was processing roughly 2,000 fraud reports daily.

The problem wasn't the app's functionality—it was the Department of Telecommunications' November 28 directive demanding that manufacturers make the app permanent, irremovable, and baked into every phone's operating system with root-level access.

Here's the thing: an app with that kind of system integration can theoretically do a lot more than check IMEIs. Privacy advocates were quick to point out that Sanchar Saathi's permissions include access to call logs, SMS messages, camera, microphone, storage, and location. The Internet Freedom Foundation called it "a permanent, non-consensual point of access sitting inside the operating system of every Indian smartphone user."

Why Apple Said No (And Samsung Stayed Quiet)

Apple doesn't do pre-installed government apps. Anywhere. This isn't India-specific stubbornness—it's a global policy that traces back to the company's famous 2016 standoff with the FBI over unlocking a terrorist's iPhone.

But Apple's refusal in India carried particular weight because of what the company represents here now.

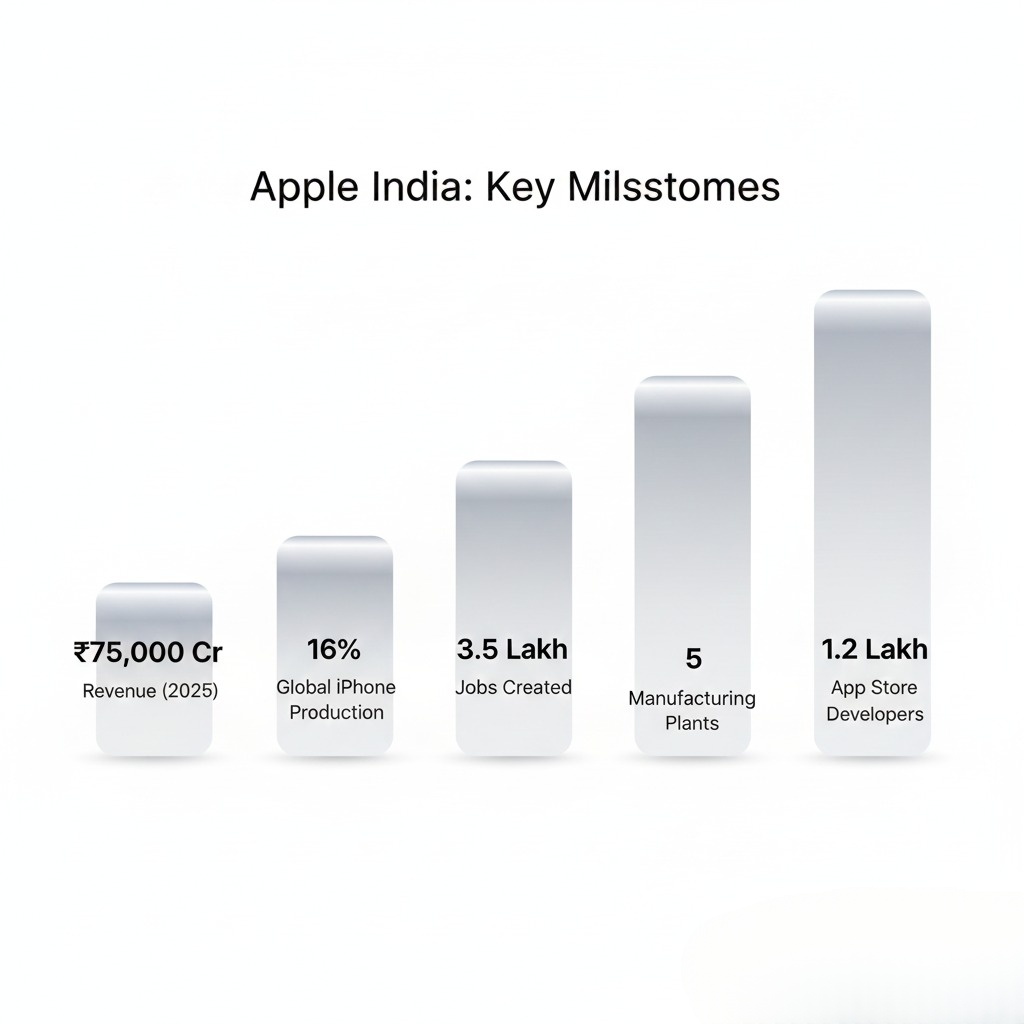

Consider the numbers: Apple's India revenue hit a record ₹75,000 crore ($9 billion) in fiscal 2025. The company shipped a record 50 lakh iPhones in Q3 2025 alone. India now produces roughly 16-17% of all iPhones globally—up from virtually nothing five years ago—with plans to hit 32% by 2027. Apple's suppliers have created nearly 3.5 lakh jobs in India, with Tata Electronics and Foxconn operating massive facilities in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

In other words, Apple isn't just selling phones in India. It's building a critical alternative to its China manufacturing base right here. And the Indian government knows this.

Samsung and Xiaomi, meanwhile, operate on Android—an open-source system that technically allows more customisation. But even they were reportedly uncomfortable with the mandate, though neither publicly opposed it the way Apple did.

The Government's Awkward Retreat

What happened next was political theatre.

On December 2, as criticism mounted from opposition parties (Congress leader Mallikarjun Kharge called the directive "akin to dictatorship") and privacy groups alike, Communications Minister Jyotiraditya Scindia insisted the app was "completely voluntary" and could be deleted anytime.

But wait. The actual directive—dated November 28 and circulated to manufacturers—explicitly stated that the app's "functionalities must not be disabled or restricted." The minister's statement directly contradicted the government's own order.

By December 3 at 3 PM, the Ministry of Communications issued a press release saying it had "decided not to make pre-installation mandatory for mobile manufacturers." The official reason? The app's "increasing acceptance"—apparently 6 lakh people downloaded it in a single day after the controversy broke.

Sure.

The real reason was simpler: Apple had called the government's bluff, and backing down was less embarrassing than forcing a showdown with a company that represents ₹70,000 crore in annual manufacturing investments.

Was Apple Ever Going to "Leave India"?

No. This was never a realistic scenario, despite what some breathless headlines suggested.

Apple leaving India would mean abandoning its fastest-growing major market, walking away from billions in manufacturing infrastructure, breaking contracts with Tata and Foxconn, and surrendering its China diversification strategy at the worst possible time (hello, Trump tariffs).

Would Apple have simply stopped selling iPhones in India rather than comply? Also unlikely. The more probable outcome, had the government not backed down, would have been months of legal challenges, quiet negotiations, and perhaps a compromise involving a downloadable-but-optional version of the app.

What Apple demonstrated was that it had enough leverage to make the first option—government retreat—the path of least resistance.

The Bigger Battle: ₹3.2 Lakh Crore on the Line

Here's what's getting less attention: Apple is simultaneously fighting a potentially massive antitrust penalty in India.

The Competition Commission of India has been investigating Apple's App Store practices since 2022, following complaints from Match Group (Tinder's parent company) and Indian startups. The CCI has preliminarily found that Apple's mandatory use of its in-app payment system constitutes "abusive conduct."

Under a 2024 amendment to India's competition law, penalties can now be calculated based on global turnover—not just Indian revenue. For Apple, with annual global sales exceeding ₹32 lakh crore ($380 billion), that means a theoretical maximum fine of ₹3.2 lakh crore ($38 billion).

Apple has challenged this penalty formula in the Delhi High Court, calling it "manifestly arbitrary, unconstitutional, grossly disproportionate, and unjust." The case is ongoing, with the CCI reportedly denying Apple's objections as recently as December 15, 2025.

What This Means for Indian Smartphone Users

For now, nothing changes. Sanchar Saathi remains a voluntary download on the App Store and Play Store. It's genuinely useful if you want to check for SIMs registered in your name or block a stolen phone.

But the episode exposed a few uncomfortable truths:

First, India's digital sovereignty ambitions will keep bumping against global tech giants' business models. The Sanchar Saathi mandate won't be the last attempt to assert control over what goes on Indian smartphones.

Second, companies like Apple have significant leverage when they're integral to government priorities like manufacturing and employment. This works both ways—it protects them from regulatory overreach but also creates dependencies that could be exploited.

Third, India still lacks a comprehensive data protection framework that would make initiatives like Sanchar Saathi more trustworthy. The app's broad permissions raised legitimate concerns precisely because there's no strong legal framework governing how that data could be used.

The Bottom Line

Apple didn't "win" against India. India didn't "lose" to Apple. What happened was a rapid recalibration once both sides realised the costs of escalation.

The government got 6 lakh new app downloads and a face-saving narrative about voluntary adoption. Apple got to maintain its global privacy stance without making a single public statement. Indian users got to keep control over what's installed on their phones.

For now.

We'll update this piece if the antitrust case produces any significant rulings or if the government revisits the pre-installation idea through different regulatory mechanisms.